Building the Missing Link Between Reasoning and Generation

Building the Missing Link Between Reasoning and Generation

At WikidataCon 2025, we presented how the Open Music Observatory is using the Wikibase Suite to connect the world of open knowledge with professional data infrastructures. This is not only about open data — it is about fixing the broken metadata plumbing that prevents both humans and AI systems from understanding our shared musical heritage.

Vectorising the Knowledge Graph

The greatest interest at WikidataCon 2025 centred on the vectorisation of knowledge graphs and the emerging Model Context Protocols (MCPs) that enable optimal cooperation between structured knowledge and large language models such as ChatGPT, Llama, Claude, and Gemini.

Knowledge graphs offer superior data integrity, context, and provenance, yet they are traditionally difficult to query and slow to adapt. Many LLMs have been trained — at least in part — on open knowledge sources such as Wikipedia and Wikidata, but they remain prone to hallucination and factual drift.

The new development frontier is therefore bridging vectorised knowledge graphs (both public and enterprise) with LLMs, allowing semantic precision to meet conversational fluency. This is how we make machine reasoning more human — and human knowledge more machine-readable.

From Silos to Sharing Spaces

Across Europe, every country maintains rich but isolated databases:

rights management systems holding data on composers and performances,

libraries with catalogued scores,

archives preserving analogue and digital recordings.

Wikidata already connects thousands of cultural databases, while Wikibase Suite allows the same logic to be applied in enterprise, institutional, or national settings.

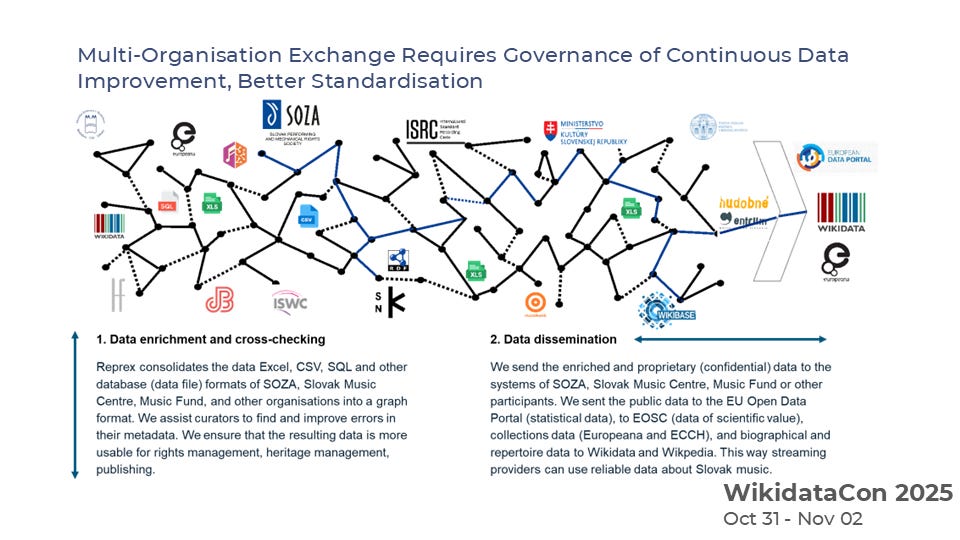

However, these systems each operate with distinct data models, governance structures, and permission rules. In the music domain, this fragmentation is particularly acute: data about a single composition — its recordings, printed scores, videos, and rights — is dispersed across publishers, labels, distributors, libraries, and rights agencies that rarely interoperate.

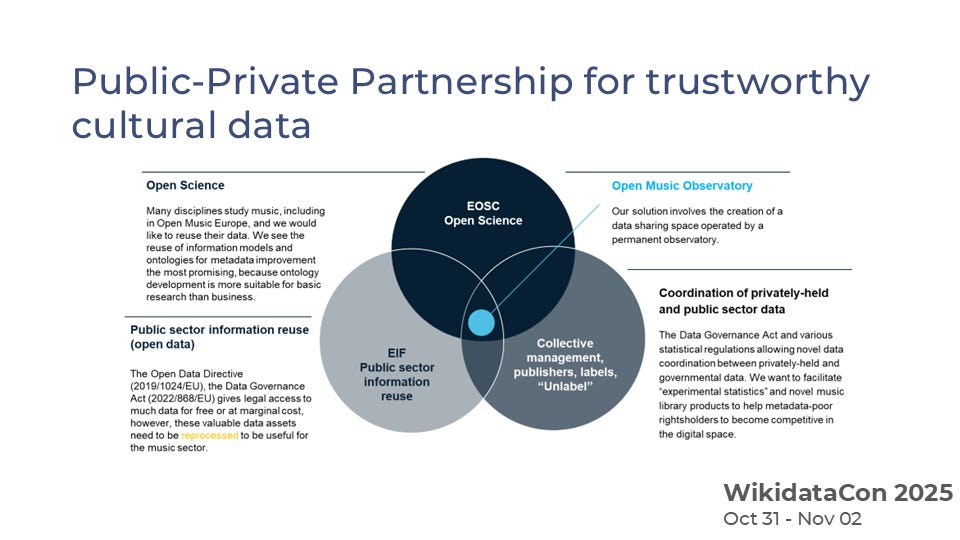

Our Open Music Observatory acts as a bridge between these silos. It connects public-sector data (from libraries, cultural registers, and public agencies) with private-sector information (from rights management organisations and streaming catalogues) through a data sharing space — a meta-database that understands the rules of each participant and mediates their data exchange.

Using Wikibase, this intermediary behaves as a translator or broker, enabling secure cross-querying while respecting ownership and access control. The result is a dynamic map of how a composer’s works appear across registries: where the scores can be borrowed, recordings streamed, or metadata corrected.

When quality and rights criteria are satisfied, verified data flows back to Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons, reinforcing the open-knowledge layer that powers both public understanding and AI learning.

In Europe, this work aligns with the Open Data Directive, which mandates that data generated by public authorities and publicly funded research be available for reuse.

Across the Atlantic, the United States follows similar principles under different legal frameworks, promoting access to high-quality, authoritative datasets from state and local agencies. Together, these open-data ecosystems form a foundational layer of trustworthy inputs for both human and machine learning.

A Staging Area for the Commons

In corporate data governance, we often speak a great deal about data protection, but far too little about data dissemination. Yet, just as companies must publish product catalogues or metadata online to enable discovery and interoperability, cultural and creative organisations also benefit from strategic openness.

Our data sharing spaces enable precisely this: controlled, rules-based data dissemination. Participating organisations can exchange verified information, improve each other’s datasets, and selectively publish metadata to the backbone of the “Internet of Data” — public graphs such as Wikidata and Wikimedia Commons.

The result is a federated flow of information between enterprise systems, national registers, and open knowledge networks.

Yet not all data can be released immediately. Some are restricted by GDPR or contractual confidentiality. Our Wikibase instances therefore act as staging areas — preparing cultural data for responsible release.

The system models temporal and legal facts: for instance, a composition enters the public domain seventy years after its author’s death. If the database can store the verified death date, this transition can propagate automatically across linked datasets.

Using the PROV and ODRL vocabularies, we encode provenance and permissions so that both humans and AI agents can reason about rights. This is where governance meets inference AI — logic layers that make creativity lawful and comprehensible.

Amplifying Minority Voices

Our Finno-Ugric and Slovak data-sharing spaces support communities whose musical heritage has been marginalised or fragmented.

From Udmurt folk rock to Mari ethnopunk, these graphs make invisible cultures computationally discoverable and connect them to contemporary audiences.

While this may appear as an esoteric or cultural preservation use case, the principle scales directly to European small and medium-sized enterprises.

Many SMEs — whether in culture, manufacturing, or design — face similar challenges: narrow markets, specialised assets, and fragmented digital presence.

Our demonstration cases therefore serve as blueprints for trustworthy AI adoption in niche cultural and business ecosystems. They illustrate how interoperable, rights-aware data architectures can strengthen both cultural heritage and commercial value chains.

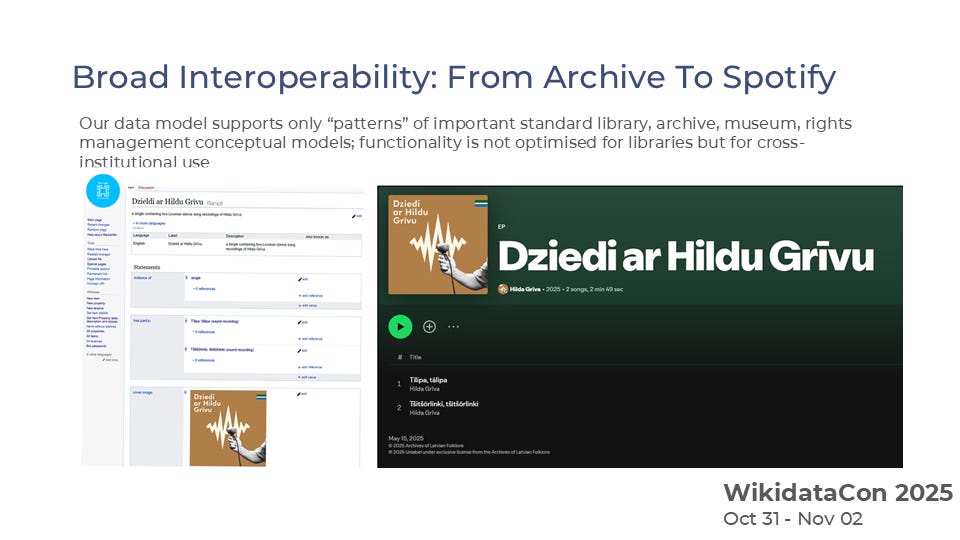

By resolving discrepancies between archival records, rights databases, and streaming catalogues, the data-sharing space enabled the lawful publication of previously inaccessible songs.

Our system is not only a passive recorder of rights — it can also update and propagate the legal status of assets within a sales or licensing pipeline.

This capability transforms metadata governance into a form of active digital rights management that benefits both artists and audiences.

Toward an Ethical Data Infrastructure

Projects such as Europeana have assembled cultural metadata painstakingly, yet at a speed far below that of today’s commercial platforms. Spotify can generate a day’s worth of new metadata in minutes.

To keep pace, Europe needs machine-readable, interoperable standards and shared environments where public and private data can coexist safely.

Wikidata and Wikibase already underpin much of the internet’s knowledge grid.

Our contribution extends that grid into the music domain, ensuring that future AI systems learn from data grounded in context, consent, and culture — the essential ingredients of responsible intelligence.

You can watch the presentation our download the entire slide deck from the event page of this conference presentation on 31 December 2025. A version of this blog is available in the Open Music Europe blog; our data sharing space was created with the support of the European Union.